Five Questions, Four Categories Of Failure, Three Paths To Forgiveness

In a perfect world, all retirement plans would be amended on time and operated properly according to the plan terms and the law. However, we don’t live in a perfect world and the IRS’s Employee Plans Compliance Resolution System (EPCRS) acknowledges that fact. EPCRS lets plan sponsors correct certain common plan failures to satisfy the plan qualification requirements without suffering the severe penalty of plan disqualification. This article provides an overview of EPCRS and how you can save a retirement plan from disqualification.

The many tax advantages of qualified retirement plans come with the responsibility for compliance with the often complex requirements of Code section 401(a) and related provisions. Qualified plans must comply both in form and in operation. Any failure to meet these obligations can lead to plan disqualification, the severe effects of which can include:

- Income taxation of the plan’s trust for all open years.

- The employer’s loss or postponement of deductions for contributions made to the plan during open tax years.

- For plan participants, immediate income taxation of vested contributions made on their behalf, or vested accrued benefits, as well as loss of their right to roll over distributions tax free to IRAs or other plans.

The IRS created EPCRS as one way to help plan sponsors avoid these consequences. EPCRS evolved over the years to its most recent version published in 2016 which, among other things, expanded the ability to correct 403(b) plan failures. Our approach to EPCRS is to ask five questions about the plan, slot any problems into the four categories of failure, and determine which of three paths to forgiveness we should take.

Five Questions

On its deceptive surface, EPCRS is a seemingly orderly set of processes that can be used by plan sponsors to “fix” retirement plans with operational and other qualification problems. Learning, using, and mastering these programs is another challenge altogether. It begins with five questions:

- What is the best way to fix operational problems?

- Are there several alternate “fixes”?

- Which program is best?

- Is the plan actually disqualified?

- Is it requalified if the IRS doesn’t specifically say so?

The IRS has not prepared (and probably cannot and never will) a comprehensive key that answers all those questions for all circumstances, problems and fixes. The IRS still retains a large amount of administrative discretion that they demystify only gradually. So plunging into the alien world of corrective compliance is not for the faint-hearted. The reality of what it takes to “requalify” a plan is learned by immersion in the programs and the facts of each plan defect.

Four Categories of Failure

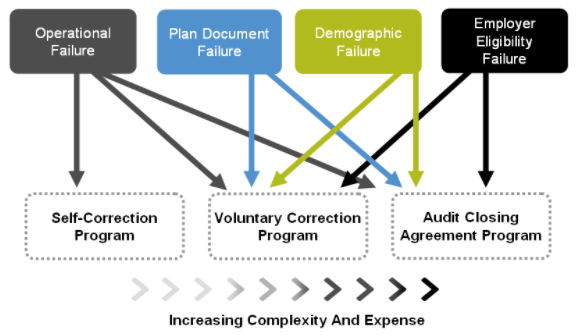

EPCRS identifies four categories of qualification failures:

- Plan document failures, where the document does not comply with the Code’s requirements, including the failure to timely adopt required amendments.

- Operational failures, where the plan was not operated according to the plan document or Code requirements.

- Demographic failures, where the plan fails minimum coverage, minimum participation or nondiscrimination testing.

- Employer eligibility failures, where the employer is not eligible to sponsor a type of retirement plan (e.g., a for-profit corporation trying to sponsor a Code section 403(b) plan).

Three Paths to Forgiveness

EPRCS consists of three parts:

- Voluntary Correction With Service Approval Program (VCP). A plan sponsor must submit an application for a compliance statement that lists the plan failures and the proposed corrections of those failures.

- Self-Correction Program (SCP). A plan sponsor may correct qualification failures without IRS involvement.

- Audit Closing Agreement Program (Audit CAP). Corrections can be made under an IRS examination.

EPCRS specifies some general correction principles applicable to each of the three parts:

- The first principle is the restoration of benefits. The correction method should restore the plan and the participants to the same position in which they would have been had the failure not occurred.

- The second principle is that corrections should be reasonable and appropriate for the failure. Depending on the nature of the failure, more than one reasonable and appropriate method of correction may be available.

- The third principle is the consistency requirement. Generally, where more than one method of correction is available to correct a failure, the correction method, including the method of determining earnings, should be applied consistently for all such failures within the same plan year and for all plan years as well.

Here is a brief description of each of the three parts.

VCP

At any time before audit, the plan sponsor may pay a limited fee and receive the IRS’s approval for corrections of a qualified plan under Code section 401(a), a Code section 403(b) plan, a SEP or a SIMPLE IRA. The compliance fee is based upon the number of plan participants and ranges from $500 for a plan with 20 or fewer participants to $15,000 for a plan with more than 10,000 participants. VCP also provides special procedures for anonymous submissions and group submissions involving the same failure in several plans administered by the same third party administrator.

Generally, the plan sponsor must submit an application to the IRS describing:

- The failures.

- How the plan sponsor proposes to correct them.

- Calculations of any corrective contributions.

- Relevant pages of plan documents related to any operational failures.

- Executed amendments or plan documents in the case of plan document failures.

EPCRS provides required VCP forms and pre-approved methods for correcting many different types of failures, including descriptions of different methods of calculating earnings that must be contributed along with corrective contributions from the time of the failure through the date of correction, (see the forms and the pre-approved corrections in the EPCRS Revenue Procedure 2016-51 at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-16.51.pdf). If a plan sponsor uses these correction methods, the plan sponsor is assured that the IRS will approve them.

However, these are not the only methods to correct many operational or demographic failures. The IRS has administrative discretion to accept other methods of correction consistent with the principles of the Code and regulations. There are times when a correction method can be negotiated with the IRS that is less expensive than the pre-approved methodology set forth in EPCRS.

SCP

SCP allows a plan sponsor that has established compliance practices and procedures to correct operational failures without needing to notify the IRS, without seeking IRS approval and without having to pay any fee or sanction. The failure may be corrected regardless of when it occurred if it is “insignificant.” If the failure is determined to be “significant,” it must be corrected within two years of the end of the plan year in which the failure occurred to be eligible for SCP and the plan must not be under audit. In order for a plan sponsor to be able to correct a significant failure in SCP, the plan sponsor must have a current determination letter (includes an IRS notice or opinion letter issued for a pre-approved plan adopted by the plan sponsor).

Obviously, it is essential to determine if, considering all of the facts and circumstances, the plan failures are significant or insignificant. The IRS has provided a long list of factors to use in weighing whether the failures are significant or insignificant, such as percentage of plan assets and contributions involved in the failure, the number of years during which the failure occurred, and the percentage of participants affected. While there are examples to illustrate these criteria, in our experience there is generally no clear, bright line test to determine if a failure is significant. It requires an analysis of the facts and circumstances and a balancing of the factors.

It is important that one properly document one’s decision regarding whether to correct under SCP or to file an application in VCP. Where this decision will be important is if the plan is audited in the future by the IRS and the IRS discovers the plan failures. If the correction under SCP was supported and properly documented, the plan will be treated as qualified. However, if the IRS determines in the audit that the failures did not qualify for SCP, you will find yourself in Audit CAP where the compliance fee is based on the taxes that would be owed if the plan were disqualified. This sanction amount in Audit CAP will be a higher amount than the compliance fee that you would have had to pay if you had applied for a compliance statement in VCP.

Correction under SCP follows the methods described under VCP, above. In addition, there are very limited circumstances where an operational failure can be selfcorrected by a retroactive plan amendment, including when a plan allowed hardship distributions or plan loans when the plan document did not allow for them, if otherwise eligible employees were allowed to enter the plan before they met the eligibility requirements, and a few other situations.

Audit CAP

Audit CAP is used by plan sponsors to correct operational failures, plan document failures and demographic failures (other than a failure corrected through SCP or VCP) discovered during an employee benefit plan audit or in a determination letter application. The plan sponsor may correct the failure and pay a sanction based upon the taxes that would be paid if the plan were disqualified for all open taxable years adjusted by a number of factors set out in the EPCRS Revenue Procedure. Negotiations in Audit CAP generally start at about 30% of this amount.

The sanction imposed will bear a reasonable relationship to the nature, extent and severity of the failure, taking into account the extent to which the correction occurred before the audit.

What to Do

So what should a plan sponsor do to ensure that its plans are in compliance with the Code’s qualification requirements? First, be on the lookout for compliance problems either in your plan document or in the operation of your plan. Second, you should become aware of the more common types of compliance problems and the ways these problems are typically corrected.

Our recommendation is to work with a qualified retirement plan professional periodically (perhaps annually in connection with nondiscrimination testing [particularly ADP/ACP testing]), and identify administrative problems identical or similar to those described on the IRS’s website. We also recommend that plan sponsors develop written administrative procedures on how to handle annual plan administration so that if there should be an operational defect, you will meet the SCP requirement that you have written administrative procedures.

The “self-correction” implication of the SCP moniker is a bit misleading. If you discover errors in your plan (hopefully before the IRS does), a good first step is to work with your benefits team advisors. Because our staff work regularly with all three programs, they are intimately familiar with the inner workings of its potential mazes, pitfalls, and benefits.

Remember, the corrections shown on the IRS’s website are not the only ways to fix the indicated failures. These are standard corrections that the IRS will always accept and they provide a nice roadmap of how to correct several of the most common operational failures.

In addition, not all failures neatly fit within the categories spelled out in EPCRS. Our staff is very experienced at negotiating with the IRS for creative and cost effective solutions for those situations.